Writing / Blog

A Bookstore Goodbye...

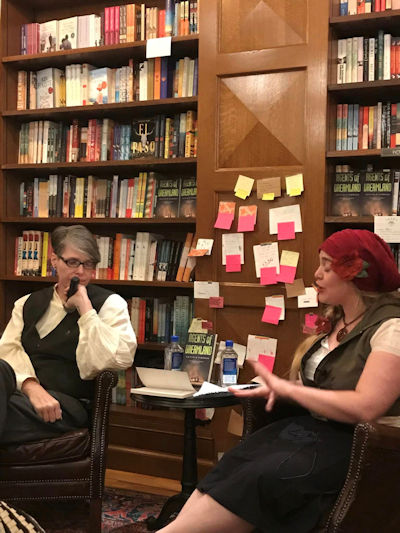

Tonight, I participated in the last event for the Savoy Bookshop

and Cafe...seven years ago, I was present at the first. I had

only recently moved back to Westerly when the Savoy opened. I

had also only recently gotten sober...and only recently starting

writing. When the Savoy opened, I was ecstatic; no longer did I

have to worry about Westerly being SO different from the big

cities in which I'd resided since last living in my hometown.

We had a bookstore! And what a bookstore it was. I marched

right in and cornered the first person I saw...Elissa Sweet.

"Hi, I'm Christa, and I'm a local writer (at the time, I barely

believed those words myself), and we're going to be friends!"

To this slightly shocked individual's credit, she immediately

put on a game face, shook my hand, and said, "That sounds

great." But she didn't JUST say "That sounds great." She was

friendly. She stuck her neck out. She introduced me to Claire

Suzanne Elizabeth Cooney. Claire introduced me to Jessica Wick.

And before I knew it, we were all friends.

Claire and Jess and Elissa changed the course of my life in Westerly. Because I'm not sure if, had I not met them when I did, and really tapped into the local writers' scene, helped along by the budding Savoy, I would have continued pursuing writing like I did. And if I hadn't pursued writing like I did, I KNOW I wouldn't have stayed sober. As my writing career progressed, I took part in so many wonderful events at the Savoy. I saw Claire's book launch for Desdemona and the Deep. I saw Carlos's event for Sal & Gabi Break the Universe. I interviewed many amazing authors. I had the launch of my short story collection at the Savoy, where I was joined by friends and family and colleagues. I interviewed the fantastic Kelly Braffet while pregnant with my daughter. We held an event for We Are Providence this past October. And since my daughter's been born, the Savoy has taken on new significance for me, as I've watched her (and our doggo, who, despite her lanky legs, destructive tail, and droopy mouth, was always welcome there, as was Maya Bear before her) eyes light up as she takes in the wonder of the place. I took for granted the idea that the Savoy would be there while Nell grew up. I hate the thought that we can no longer take our almost weekly jaunts there. I wanted her to be able to peer into the depths of those magical portals lining the maze-like shelves – and into those fairy doors – forever.

I know things change. I know nothing can stay the same. Things and places can die just like people do. The important thing is the stories we DID take from the Savoy. And the people we met there. The connections we made. They're still going strong. As will, I imagine, the memories of the wonderful, magical place that brought us together.

– Christa Carmen

July 27, 2023

Claire and Jess and Elissa changed the course of my life in Westerly. Because I'm not sure if, had I not met them when I did, and really tapped into the local writers' scene, helped along by the budding Savoy, I would have continued pursuing writing like I did. And if I hadn't pursued writing like I did, I KNOW I wouldn't have stayed sober. As my writing career progressed, I took part in so many wonderful events at the Savoy. I saw Claire's book launch for Desdemona and the Deep. I saw Carlos's event for Sal & Gabi Break the Universe. I interviewed many amazing authors. I had the launch of my short story collection at the Savoy, where I was joined by friends and family and colleagues. I interviewed the fantastic Kelly Braffet while pregnant with my daughter. We held an event for We Are Providence this past October. And since my daughter's been born, the Savoy has taken on new significance for me, as I've watched her (and our doggo, who, despite her lanky legs, destructive tail, and droopy mouth, was always welcome there, as was Maya Bear before her) eyes light up as she takes in the wonder of the place. I took for granted the idea that the Savoy would be there while Nell grew up. I hate the thought that we can no longer take our almost weekly jaunts there. I wanted her to be able to peer into the depths of those magical portals lining the maze-like shelves – and into those fairy doors – forever.

I know things change. I know nothing can stay the same. Things and places can die just like people do. The important thing is the stories we DID take from the Savoy. And the people we met there. The connections we made. They're still going strong. As will, I imagine, the memories of the wonderful, magical place that brought us together.

– Christa Carmen

July 27, 2023

When the Looking Glass Looks Back

The catalyst, for me, for writing a piece of short horror fiction

used to be anything from an interest in playing with overdone

tropes to the desire to write an entire piece around a particularly

macabre or striking image. Today, the formula is much simpler:

muse on something that scares you and go from there. In

2023, there is no shortage of horrifying headlines from which to

pluck, and as a still-new mother, the micro-level fears are just

as abundant.

But one topic is able to worm its way into my heart like a maggot into an apple no matter how much time passes, and it's this fear I explored in my contribution to Wicked Run Press's Orphans of Bliss: Tales of Addiction Horror, edited by Mark Matthews. "Through the Looking Glass and Straight into Hell" doesn't ask, "What would happen if you relapsed after so much time being clean?" but, "What if everything you think you've accomplished since getting clean never happened at all?"

On the Fourth of July in 2013, I was sitting in a rehab facility, writing in a journal, oblivious to the fact that I was one week away from my first of three opioid overdoses. "Why does it seem so much easier to use than to stay clean?" I wrote, digging into the page so hard that the pen left divots. And then, after a group counseling session in which the topic was focusing on the future, I wrote: "Visualize the life you want...Ok, what do I want?"

It's a question that patients/clients in substance abuse treatment facilities are asked constantly over the course of their treatment, encouraged by counselors to maintain early sobriety by imagining all the things they could achieve if they keep that sobriety intact. Past successes are held up us as evidence of future potential. Statements like, "You could be/do/have/accomplish anything if only you'd put down the drugs and alcohol" abound.

I was resistant to these entreaties, and I have the journals to prove it. I filled page after page with lines like, "I want to get high so badly right now," likened my white-knuckled sober time to the plot of The Life of Pi, claiming refraining from using was like sharing a lifeboat with a tiger waiting to spring, and plotted out elaborate fantasies where I escaped detox to go on a run, one of which was successfully carried out. I ridiculed the myriad doctors, nurses, and counselors trying to get through to me; didn't they know that in my brain (and here I'll take another unaltered line from my journal), "in the place where the actual battle was being waged, I had already bowed down, and it was the hazel-green of the tiger that flashed out whenever light shone in the damp, mud-brown pools of my eyes?"

But eventually, I did do what the doctors and counselors wanted to see from their patients: I stacked one small, hard-won victory on top of another. First, of course, I stayed clean and sober. Everything relied on that. But then I cleared up my suspended driver's license (and other legal issues), moved back to Rhode Island, found a job, and then a second one. I met someone who supported me and my recovery, repaired relationships with my family members, and started pursuing writing as a hobby (and then, started writing in a way that was more than a hobby).

Now, it has been ten years after my last intake at a substance abuse facility. I am married, recently signed a two-book deal for my debut and second novels, and have a daughter who lights up my world in ways I never dreamed possible. Numerous times on the journey to get to where I am today, I would think back to those days in various substance abuse facilities, where I passed the time wondering if any life I could imagine would be worth making so many painful changes. It seemed not just an insurmountable task, but a Sisyphean one, that a return to whatever detox or counseling session from where I pondered the future would be inevitable.

And the belief that relapse was inevitable gave my mental grasps at the future a strange, dream-logic quality. Every future I envisioned had the sense of a play I'd been granted a (very temporary) role in, and this phenomenon extended so far as to color each attempt at early sobriety outside of my imagination, too. I could think and say and act as I pleased fresh out of the gate of rehab because, undoubtedly, I would be back. And it was a revolving door, until it occurred to me that, one day very soon, there would be no more second chances.

I could write further about the connection between how I felt, ten years ago, embarking on the sober life that finally stuck, and the genesis of "Through the Looking Glass and Straight into Hell," but I think I'd do better to reprint a poem I wrote not long after leaving rehab for the last time. For anyone who's read the story, I'm confident you will see its seeds within these stanzas. Not only are the thematic connections strong, but the physical object of a (rather creepy) mirror recurs from one piece to the next.

(A caveat: I write predominately prose and have not edited this poem; I include it unchanged from how it appeared when my writing was far FAR less about skill and far more about capturing the way I was feeling that very second. I don't harbor any delusions that this piece would be accepted into any worthwhile publication, but I DO think there's tangible power within its lines all the same – especially in the very last stanza).

Mold in the Mirror

When you look in the mirror,

the reflection shimmers

until the image within is a strange, inverted version of you.

Not even 'you' –

not the 'you' you know now,

but the 'you' that existed in a vacuum.

Devoid of light, devoid of friends,

devoid of peace and of fun and

completely devoid of truth.

The lie you told yourself every morning

when you woke up and looked into that mirror:

"Everything's ok," and "you are in control."

You'd fix your hair, maybe, and fix

your face and your teeth

And make yourself as presentable

to the world as you could; but the lie was there.

No control. Control might as well

have been spelled 'd-e-l-u-s-i-o-n,'

And you'd been in bed with

that delusion, as glued together and

torrid as an extramarital affair.

No break. The proverbial monkey

on your back, an eight-hundred-pound gorilla.

Following you into the blackest alleys

and whispering into your ear.

When you catch another glimpse into

that mirror, an unexpected peek

between the breaks in your veneer,

you think, I could go back.

And you could go back. It wouldn't

take much. In fact, it would take

so little to return to the old you, that it's

frightening.

Jarring. One backpack. Some cash.

The car. The shirt on your back.

A phone, maybe. Maybe not even

a phone. A steadfast commitment to

self-destruction.

Demolition. Kicking the pieces out, brick-by-brick.

You can feel the foundation trembling.

See the mold in the mirror.

So you reach out,

and steady your reflection,

in the glass.

Thank you to everyone who has read Orphans of Bliss, and my contribution to it, and left a review or thought it worthy to recommend for the 2022 Bram Stoker Awards® reading list. If you'd like to read the story, please reach out to me directly, and I'll be happy to provide you with a copy.

– Christa Carmen

February 12, 2023

But one topic is able to worm its way into my heart like a maggot into an apple no matter how much time passes, and it's this fear I explored in my contribution to Wicked Run Press's Orphans of Bliss: Tales of Addiction Horror, edited by Mark Matthews. "Through the Looking Glass and Straight into Hell" doesn't ask, "What would happen if you relapsed after so much time being clean?" but, "What if everything you think you've accomplished since getting clean never happened at all?"

On the Fourth of July in 2013, I was sitting in a rehab facility, writing in a journal, oblivious to the fact that I was one week away from my first of three opioid overdoses. "Why does it seem so much easier to use than to stay clean?" I wrote, digging into the page so hard that the pen left divots. And then, after a group counseling session in which the topic was focusing on the future, I wrote: "Visualize the life you want...Ok, what do I want?"

It's a question that patients/clients in substance abuse treatment facilities are asked constantly over the course of their treatment, encouraged by counselors to maintain early sobriety by imagining all the things they could achieve if they keep that sobriety intact. Past successes are held up us as evidence of future potential. Statements like, "You could be/do/have/accomplish anything if only you'd put down the drugs and alcohol" abound.

I was resistant to these entreaties, and I have the journals to prove it. I filled page after page with lines like, "I want to get high so badly right now," likened my white-knuckled sober time to the plot of The Life of Pi, claiming refraining from using was like sharing a lifeboat with a tiger waiting to spring, and plotted out elaborate fantasies where I escaped detox to go on a run, one of which was successfully carried out. I ridiculed the myriad doctors, nurses, and counselors trying to get through to me; didn't they know that in my brain (and here I'll take another unaltered line from my journal), "in the place where the actual battle was being waged, I had already bowed down, and it was the hazel-green of the tiger that flashed out whenever light shone in the damp, mud-brown pools of my eyes?"

But eventually, I did do what the doctors and counselors wanted to see from their patients: I stacked one small, hard-won victory on top of another. First, of course, I stayed clean and sober. Everything relied on that. But then I cleared up my suspended driver's license (and other legal issues), moved back to Rhode Island, found a job, and then a second one. I met someone who supported me and my recovery, repaired relationships with my family members, and started pursuing writing as a hobby (and then, started writing in a way that was more than a hobby).

Now, it has been ten years after my last intake at a substance abuse facility. I am married, recently signed a two-book deal for my debut and second novels, and have a daughter who lights up my world in ways I never dreamed possible. Numerous times on the journey to get to where I am today, I would think back to those days in various substance abuse facilities, where I passed the time wondering if any life I could imagine would be worth making so many painful changes. It seemed not just an insurmountable task, but a Sisyphean one, that a return to whatever detox or counseling session from where I pondered the future would be inevitable.

And the belief that relapse was inevitable gave my mental grasps at the future a strange, dream-logic quality. Every future I envisioned had the sense of a play I'd been granted a (very temporary) role in, and this phenomenon extended so far as to color each attempt at early sobriety outside of my imagination, too. I could think and say and act as I pleased fresh out of the gate of rehab because, undoubtedly, I would be back. And it was a revolving door, until it occurred to me that, one day very soon, there would be no more second chances.

I could write further about the connection between how I felt, ten years ago, embarking on the sober life that finally stuck, and the genesis of "Through the Looking Glass and Straight into Hell," but I think I'd do better to reprint a poem I wrote not long after leaving rehab for the last time. For anyone who's read the story, I'm confident you will see its seeds within these stanzas. Not only are the thematic connections strong, but the physical object of a (rather creepy) mirror recurs from one piece to the next.

(A caveat: I write predominately prose and have not edited this poem; I include it unchanged from how it appeared when my writing was far FAR less about skill and far more about capturing the way I was feeling that very second. I don't harbor any delusions that this piece would be accepted into any worthwhile publication, but I DO think there's tangible power within its lines all the same – especially in the very last stanza).

Mold in the Mirror

When you look in the mirror,

the reflection shimmers

until the image within is a strange, inverted version of you.

Not even 'you' –

not the 'you' you know now,

but the 'you' that existed in a vacuum.

Devoid of light, devoid of friends,

devoid of peace and of fun and

completely devoid of truth.

The lie you told yourself every morning

when you woke up and looked into that mirror:

"Everything's ok," and "you are in control."

You'd fix your hair, maybe, and fix

your face and your teeth

And make yourself as presentable

to the world as you could; but the lie was there.

No control. Control might as well

have been spelled 'd-e-l-u-s-i-o-n,'

And you'd been in bed with

that delusion, as glued together and

torrid as an extramarital affair.

No break. The proverbial monkey

on your back, an eight-hundred-pound gorilla.

Following you into the blackest alleys

and whispering into your ear.

When you catch another glimpse into

that mirror, an unexpected peek

between the breaks in your veneer,

you think, I could go back.

And you could go back. It wouldn't

take much. In fact, it would take

so little to return to the old you, that it's

frightening.

Jarring. One backpack. Some cash.

The car. The shirt on your back.

A phone, maybe. Maybe not even

a phone. A steadfast commitment to

self-destruction.

Demolition. Kicking the pieces out, brick-by-brick.

You can feel the foundation trembling.

See the mold in the mirror.

So you reach out,

and steady your reflection,

in the glass.

Thank you to everyone who has read Orphans of Bliss, and my contribution to it, and left a review or thought it worthy to recommend for the 2022 Bram Stoker Awards® reading list. If you'd like to read the story, please reach out to me directly, and I'll be happy to provide you with a copy.

– Christa Carmen

February 12, 2023

Today is Maya's birthday...

If it were any other year, I'd have taken her for a walk by the beach, or else along the streets that meander around No Bottom Pond, a neighborhood where we were once berated by a woman mistakenly convinced that Maya had gone to the bathroom on her lawn. One of my first – albeit terrible – short horror stories was inspired by the incident, and the comeuppance that would result from such an accusation. Maya didn't understand the story's thinly-veiled metaphors, but she did appreciate the gleeful encouragement and graciously long lead I gave her in the empty lot next to the woman's house ever since.

In addition to the walk, I would have baked a batch of peanut butter cupcakes, a recipe I've made every February 6th for the last twelve years. Maya would sit in her bed beneath the butcher block in my kitchen, made patient by the familiarity of the ingredients and her subsequent certainty the concoction was for her. I would have presented her with bone-and pawprint gift bags, fleece blankets and stuffed bunnies poking conspicuously from the tops, then helped her nose past the ribbon and tissue paper to unearth the prizes within.

I would have ended the day like any other, birthday or random Saturday night: by tucking her in beneath a mountain of blankets, pulling gently on her ears, kissing her between her amber-colored eyes, and telling her how much I loved her.

This February 6th, I will do none of these things. Instead, I will persist in my imitation of someone shipwrecked, thirsting, wandering. I will curl into balls on empty dog beds, press abandoned stuffed animals to my face, seeking comfort from their painfully inanimate forms. I will continue all of the useless, excruciating, heartsick distractions I've been engaged in for the past two weeks, from the moment Maya took her last breath on a bed in my house, her head nestled against my chest. I will stare at the spaces on window seats and depressions on couches, wondering confusedly how they can be so empty. I will freeze before the sink, suddenly convinced that I've heard her, a contented sigh or the soft clicking of her toenails, only to find it's the radiators, or the fish tank, or my own imagination, desperate and grasping at ghosts.

Just two weeks before this, a lump appeared on Maya's back leg, literally overnight. An aspirate at the vet's office two days later showed the lump to be a mast cell tumor.

"Chemotherapy is one option," the doctor told me, "but there are holistic treatments shown to produce positive results as well." The vet also stated the tumor was inoperable due to its "wide margins" across the top of her leg. In the space of a five minute phone call, I was forced to confront the possibility of a different ending to Maya's story. My brain sputtered and balked, trying – and failing – to conceptualize a future in which words like "cancer" and "treatment options" replaced "road trips" and "old age."

Maya had experienced numerous health issues as a younger dog, from chronic bladder infections to seizures and pancreatitis. Once I started feeding her a homemade diet of lean meat, puréed vegetables, and a dozen different nutritional supplements and vitamins, every single problem vanished, never to return again. She even lost that pesky beagle weight our daily three-mile walk had never touched. She was declared in perfect health by every vet tech and doctor who saw her. Fellow dog owners expressed surprise when I told them her age. In addition to my foolish belief in some equitable distributor of canine maladies, I fell for the cruelest trick of all, that is, believing that my absolute love for another being had become some sort of protection spell, shielding her from harm.

I trusted – the way I trust the stars will appear at night or that the rainy days of spring will eventually give way to summer – that Maya would live to be twenty. Hearing that her cancer had already progressed to the worst possible grade was like being told there were zombies lumbering up the driveway or vampires hanging from the rafters in the attic. Unfortunately, Maya's symptoms grew worse so quickly, I had no choice but to adapt to this nightmarish reality.

On Thursday, a week and a half after the tumor appeared, Maya stopped eating and drinking. I lay next to her on the daybed in my home office, tracking her uneven, shuddering breaths while on hold with the emergency clinic. I was told to bring her in as soon as possible; we arrived within the hour.

I sat in the car outside the clinic, cursing COVID for preventing me from going inside. The minutes ticked past. I called for an update and was told it might be best if I waited at home. Pollyanna that I was, I still thought they'd just give her some fluids and I'd pick her up that afternoon. She couldn't be that sick yet. Even dogs with high grade, aggressive tumors could live for four to six months. It must have been the stasis breaker powder or mushroom capsules the holistic vet prescribed upsetting her stomach.

But the next time I called, I received surprising news: Maya's condition was poor enough that it warranted her staying the night. The vet overseeing her care told me she was dehydrated and weak from vomiting, her stomach painful to the touch. They wanted to schedule an ultrasound first thing the next morning. "That will tell us if the cancer has spread. If it hasn't," the vet said, her tone cautiously optimistic, "I can schedule a surgical consultation."

"It's operable?" I asked, shocked this was even a possibility after our primary vet's prognosis.

"That's for a surgeon to decide, but the location of the tumor means it's technically conducive to removal." The optimism left her voice. "Even if the tumor is able to be removed, if the cancer has spread, we wouldn't put a dog through that kind of surgery."

Her implication was clear. "I understand," I said, "I'll await your phone call tomorrow." I gave my permission and payment information for the ultrasound, and hung up the phone.

In the past, if I had to go out of town, or came home late and Maya spent the night at my parents', her absence from my bed left me out of sorts. Despite her having to remain at the ER, the knowledge that her tumor might be operable provided me with a small measure of comfort over the many times I awoke that night.

That hope was short-lived. Friday morning, a new veterinarian, Dr. Sun, called with the results of Maya's ultrasound. The cancer had metastasized. It'd spread to her lymph nodes. They suspected it was in her spleen. "We've stabilized her, and if she continues to hold down food, we could discharge her early this evening."

My options were now euthanasia due to the fact that her condition was terminal, chemotherapy plus radiation (in light of the ultrasound results, chemotherapy on its own wouldn't be effective), or take her home with a prescription for a steroid. With the third option, she'd have days, maybe weeks, to live.

"How much time would chemo and radiation get us?"

"Three months," Dr. Sun replied. "Maybe less."

I swallowed. I couldn't justify putting her through that invasive and, to a dog, inexplicable of a treatment. It would be selfish to condemn her to weekly injections and – with the radiation – anesthesia. "I would like to take her home," I choked out. "I need to take her home." It felt like a bulbous, ice-cold stone had lodged between my sternum and heart.

"Very good," Dr. Sun responded. She paused, and then said kindly, "I think that's the best choice, taking Maya home."

My father drove me back to East Greenwich to pick Maya up since my husband was still at work and I was too upset to drive. We waited in the car until a tech brought her out. I fumbled with my mask, scrambling to hook it behind my ears. While the tech went over the same discharge instructions the doctor told me over the phone, I nodded, but had trouble focusing on what she said. I hadn't eaten. A migraine was building behind my eyes. I wanted her to stop talking so I could get Maya out of the cold and into the car.

When she did hand me the leash, I thanked her, kneeled down, and scooped Maya up. I placed her as gently as possible into a bed on the backseat. She sat awkwardly, favoring her bandaged front paw. She looked as if she wasn't sure what she was supposed to do. I got in next to her and patted the blankets. She laid down heavily, her chin resting on my hand. I placed my other hand on her head, and as the grey day and greyer trees whizzed by, this was how I held her.

I was lost in thirteen years of memories when my father gestured at the windshield. "Chris, look at the sunset."

The sky belonged to some other, kinder world, the peach and violet layers shot through with glittering gold. I stared at it hard, trying to ascribe some greater meaning. Hope? Peace? No. It was just a sky. The highway veered slightly to the right and the colors lost their luster. I should have taken a picture when I had the chance. It was there one minute, and gone the next; beautiful but fleeting.

Perhaps there was greater meaning there after all.

As we pulled onto my long driveway, I stroked her face and nose, my hand tracing the delicate curvature of her head. I didn't know what the upcoming days – or weeks, if we were lucky – would bring, but for now, all that mattered was we were home.

In addition to the walk, I would have baked a batch of peanut butter cupcakes, a recipe I've made every February 6th for the last twelve years. Maya would sit in her bed beneath the butcher block in my kitchen, made patient by the familiarity of the ingredients and her subsequent certainty the concoction was for her. I would have presented her with bone-and pawprint gift bags, fleece blankets and stuffed bunnies poking conspicuously from the tops, then helped her nose past the ribbon and tissue paper to unearth the prizes within.

I would have ended the day like any other, birthday or random Saturday night: by tucking her in beneath a mountain of blankets, pulling gently on her ears, kissing her between her amber-colored eyes, and telling her how much I loved her.

This February 6th, I will do none of these things. Instead, I will persist in my imitation of someone shipwrecked, thirsting, wandering. I will curl into balls on empty dog beds, press abandoned stuffed animals to my face, seeking comfort from their painfully inanimate forms. I will continue all of the useless, excruciating, heartsick distractions I've been engaged in for the past two weeks, from the moment Maya took her last breath on a bed in my house, her head nestled against my chest. I will stare at the spaces on window seats and depressions on couches, wondering confusedly how they can be so empty. I will freeze before the sink, suddenly convinced that I've heard her, a contented sigh or the soft clicking of her toenails, only to find it's the radiators, or the fish tank, or my own imagination, desperate and grasping at ghosts.

Just two weeks before this, a lump appeared on Maya's back leg, literally overnight. An aspirate at the vet's office two days later showed the lump to be a mast cell tumor.

"Chemotherapy is one option," the doctor told me, "but there are holistic treatments shown to produce positive results as well." The vet also stated the tumor was inoperable due to its "wide margins" across the top of her leg. In the space of a five minute phone call, I was forced to confront the possibility of a different ending to Maya's story. My brain sputtered and balked, trying – and failing – to conceptualize a future in which words like "cancer" and "treatment options" replaced "road trips" and "old age."

Maya had experienced numerous health issues as a younger dog, from chronic bladder infections to seizures and pancreatitis. Once I started feeding her a homemade diet of lean meat, puréed vegetables, and a dozen different nutritional supplements and vitamins, every single problem vanished, never to return again. She even lost that pesky beagle weight our daily three-mile walk had never touched. She was declared in perfect health by every vet tech and doctor who saw her. Fellow dog owners expressed surprise when I told them her age. In addition to my foolish belief in some equitable distributor of canine maladies, I fell for the cruelest trick of all, that is, believing that my absolute love for another being had become some sort of protection spell, shielding her from harm.

I trusted – the way I trust the stars will appear at night or that the rainy days of spring will eventually give way to summer – that Maya would live to be twenty. Hearing that her cancer had already progressed to the worst possible grade was like being told there were zombies lumbering up the driveway or vampires hanging from the rafters in the attic. Unfortunately, Maya's symptoms grew worse so quickly, I had no choice but to adapt to this nightmarish reality.

On Thursday, a week and a half after the tumor appeared, Maya stopped eating and drinking. I lay next to her on the daybed in my home office, tracking her uneven, shuddering breaths while on hold with the emergency clinic. I was told to bring her in as soon as possible; we arrived within the hour.

I sat in the car outside the clinic, cursing COVID for preventing me from going inside. The minutes ticked past. I called for an update and was told it might be best if I waited at home. Pollyanna that I was, I still thought they'd just give her some fluids and I'd pick her up that afternoon. She couldn't be that sick yet. Even dogs with high grade, aggressive tumors could live for four to six months. It must have been the stasis breaker powder or mushroom capsules the holistic vet prescribed upsetting her stomach.

But the next time I called, I received surprising news: Maya's condition was poor enough that it warranted her staying the night. The vet overseeing her care told me she was dehydrated and weak from vomiting, her stomach painful to the touch. They wanted to schedule an ultrasound first thing the next morning. "That will tell us if the cancer has spread. If it hasn't," the vet said, her tone cautiously optimistic, "I can schedule a surgical consultation."

"It's operable?" I asked, shocked this was even a possibility after our primary vet's prognosis.

"That's for a surgeon to decide, but the location of the tumor means it's technically conducive to removal." The optimism left her voice. "Even if the tumor is able to be removed, if the cancer has spread, we wouldn't put a dog through that kind of surgery."

Her implication was clear. "I understand," I said, "I'll await your phone call tomorrow." I gave my permission and payment information for the ultrasound, and hung up the phone.

In the past, if I had to go out of town, or came home late and Maya spent the night at my parents', her absence from my bed left me out of sorts. Despite her having to remain at the ER, the knowledge that her tumor might be operable provided me with a small measure of comfort over the many times I awoke that night.

That hope was short-lived. Friday morning, a new veterinarian, Dr. Sun, called with the results of Maya's ultrasound. The cancer had metastasized. It'd spread to her lymph nodes. They suspected it was in her spleen. "We've stabilized her, and if she continues to hold down food, we could discharge her early this evening."

My options were now euthanasia due to the fact that her condition was terminal, chemotherapy plus radiation (in light of the ultrasound results, chemotherapy on its own wouldn't be effective), or take her home with a prescription for a steroid. With the third option, she'd have days, maybe weeks, to live.

"How much time would chemo and radiation get us?"

"Three months," Dr. Sun replied. "Maybe less."

I swallowed. I couldn't justify putting her through that invasive and, to a dog, inexplicable of a treatment. It would be selfish to condemn her to weekly injections and – with the radiation – anesthesia. "I would like to take her home," I choked out. "I need to take her home." It felt like a bulbous, ice-cold stone had lodged between my sternum and heart.

"Very good," Dr. Sun responded. She paused, and then said kindly, "I think that's the best choice, taking Maya home."

My father drove me back to East Greenwich to pick Maya up since my husband was still at work and I was too upset to drive. We waited in the car until a tech brought her out. I fumbled with my mask, scrambling to hook it behind my ears. While the tech went over the same discharge instructions the doctor told me over the phone, I nodded, but had trouble focusing on what she said. I hadn't eaten. A migraine was building behind my eyes. I wanted her to stop talking so I could get Maya out of the cold and into the car.

When she did hand me the leash, I thanked her, kneeled down, and scooped Maya up. I placed her as gently as possible into a bed on the backseat. She sat awkwardly, favoring her bandaged front paw. She looked as if she wasn't sure what she was supposed to do. I got in next to her and patted the blankets. She laid down heavily, her chin resting on my hand. I placed my other hand on her head, and as the grey day and greyer trees whizzed by, this was how I held her.

I was lost in thirteen years of memories when my father gestured at the windshield. "Chris, look at the sunset."

The sky belonged to some other, kinder world, the peach and violet layers shot through with glittering gold. I stared at it hard, trying to ascribe some greater meaning. Hope? Peace? No. It was just a sky. The highway veered slightly to the right and the colors lost their luster. I should have taken a picture when I had the chance. It was there one minute, and gone the next; beautiful but fleeting.

Perhaps there was greater meaning there after all.

As we pulled onto my long driveway, I stroked her face and nose, my hand tracing the delicate curvature of her head. I didn't know what the upcoming days – or weeks, if we were lucky – would bring, but for now, all that mattered was we were home.

#

When I adopted Maya as a seven week old, five pound puppy, "home" was my parents' house in Rhode Island. I was newly sober, staying there while I figured out my next move, applying to master's programs in counseling. I settled on Boston College, and when I moved to Chestnut Hill a few months later, Maya, and her maroon BC sweater, were in tow.

During that first year in Boston, I relapsed hard and often. I nurtured an eating disorder, toxic friendships, bad boyfriends. But whether hungover or...more hungover, rain or shine, I took Maya for a walk every day. I never missed a vet visit and bought expensive, organic dog food. I refused to leave her alone for more than a few hours each day. We moved to South Boston, then Revere, then briefly, New Hampshire, then back to Rhode Island after the ability to get sober again had completely fallen out of my hands. During that time, Maya was often the only thing that kept me tethered to real life, real responsibilities, real people; Maya was often the only thing that kept me tethered to the earth at all.

Slowly, the lessons I'd learned from my first bout of sobriety returned to me, then began to stick. I didn't go to meetings religiously or complete the twelve steps, but I did the things that worked for me, Maya by my side. It is only now, contemplating these last seven years of sobriety, that I realized I learned how to take care of myself by taking care of her.

In 2013, Maya and I moved in with my now-husband. Three years later, we bought a house. It's cozy and quiet and surrounded by trees, with a big bay front window that Maya claimed as her own. I wasted no time potting plants and hanging a kitchen witch, picking out curtains and laying down rugs. But the transition from house to home was actualized when there was a bed for Maya in every room. At least that's what I thought at the time. It was only when returning to my house from the ER with Maya beside me that I realized the truth of the past thirteen years.

Throughout all the cities, the apartments, the rehab facilities, the moving in with my parents and venturing out again, there was one constant, one heart, one hearth. Home was never something I left or returned to, never something I needed to find. It might sound trite, but it's probably the truest statement of my tumultuous twenties, the crux of figuring out who I was without drugs or booze. "Home" was with me whether apartment complex or basement, brownstone or starter house, regardless of the curtains or the dog beds, step by – excruciating, wonderful, or otherwise – step. It was Maya herself that had always been my home.

#

I slept on the daybed in my office with Maya that night, and while her extreme lethargy was troubling, the next morning I was optimistic again. She gobbled grilled chicken with close to her usual gusto, then begged for an Eggo, which I readily fed her by hand. She was alert, even happy, and I decided she was up for a drive across town to visit my parents (and sister, who was visiting from Miami) for the day.

Maya curled up in her car seat and seemed to enjoy the sun on her face as she peered out at the cold, clear world. My mother had Maya's favorite homemade biscuits cooling on the counter when we arrived, and Maya took one, and then another. But again, my hope in her feeling better was short-lived. Around noon, she went to the door, and I saw with horror that her knee beneath the tumor had ballooned to three times its normal size. I took her outside and she went to the bathroom, but was having trouble walking. When we returned, she wouldn't take any more food, though I offered her everything in the refrigerator. Soon after, the shaking that caused me to take her to the ER began again in earnest.

She became disoriented. Listless. There were additional negative symptoms, ugly things one associates with the end. Worse, she wanted only to go outside and wander aimlessly. It was brutally cold, but I donned my jacket time and time again. She finally settled into her bed when I moved it by the door. I dragged a blanket and pillow over and laid down beside her.

While she drifted in and out of fitful sleep, I alternated stroking her neck with telling her stories. I reminded her of friends she'd known, trips we'd taken, walks that defined periods of our lives. The sun sank lower and lower beneath the branches of skeletal trees. The space where we laid beside the door grew colder. I tried to take in every detail of her face, so as to hold them forever in my mind and heart. It was the last unbroken hour I ever spent with her. Later, back home, a mobile veterinarian, Dr. Washburn, who was truly wonderful, arrived.

I will keep that time locked away in my heart as well. When Maya is gone, I find I cannot comprehend it. The space she's left behind is an impossibility, an incongruence, a chasm larger than the physical boundaries of my house or the metaphysical ones of my brain. My husband orders Chinese food but I cannot eat it. I sit numbly on the couch. My eyes feel as if they've floated away on rivers of fire. My stomach is riddled with knots.

I cry myself to sleep. Somehow, the night passes. Then another. The days are hollow, three times their actual length. I think I hear her everywhere. Just out of reach. In the next room. Behind me. If I'm home, yet she's not, she must be with my husband or at my parents', waiting for me to pick her up. Following these thoughts, which fire via automatic, split-second transmissions, there are drawn-out valleys of remembering and despair.

There are so many small moments of my day I don't know how to fill, moments between the "bigger," more important tasks of my day. Moments in which I filled her water bowl or fluffed her blankets or took her outside to stare at birds and sniff the air. Or else moments in which I'd go to her in her big bay front window to kiss her muzzle and pull her ears.

Maya was the glue that held my day together, that connected one moment to the next. Now I am unmoored, crushed by the silence and the weight of my grief, heavy as the ocean and just as vast. I continue to fill her water dish. I cannot bear to see it empty. I can't tell if this makes me feel better or worse.

The days go by. The pain has not lessened. I get angry and make deals with the devil: I'll trade you all seven of the chickens to have Maya back; I'll give you every dog in this neighborhood for another year with mine. There is no teachable moment, no point to this essay. I do not want another dog. How would I even take comfort from such a thing? I don't like other people's dogs; I am not a dog person. I was a Maya person, and Maya's gone.

I've never been much of a believer in heaven. It seems too much a fairy tale for adults. Rather, I seem to have subscribed to the atheist, naturalist belief that we become part of the ground in which we are buried. If that is the case, I do so hope that the oak tree my body nourishes grows up toward the sky next to Maya's birch or elm. But I will also say this: if I am wrong, and there is a heaven, some place as grand as human beings have imagined, what a truly wonderful thing to once again kneel before Maya and ruffle the fur on her head. I would pull gently on her ears, kiss her between her amber-colored eyes, and tell her how much I love her.

I would fill her in on what she's missed, and ask if she's pissed off any rich Watch Hill women by pretend-peeing on their lawn. She would dance around my legs happily, then lead me to her new, far bigger window seat. I would remember how much I missed the sound of her toenails clicking, the feel of her whiskers against my palm. I would ask her if she wanted to go for a walk or eat cupcakes, or simply curl up next to her, the weight of her body against my feet. Despite a great many years, miles, addresses, heartaches, I would finally be home.

Until then, happy birthday, Nugget.

Book Showcase

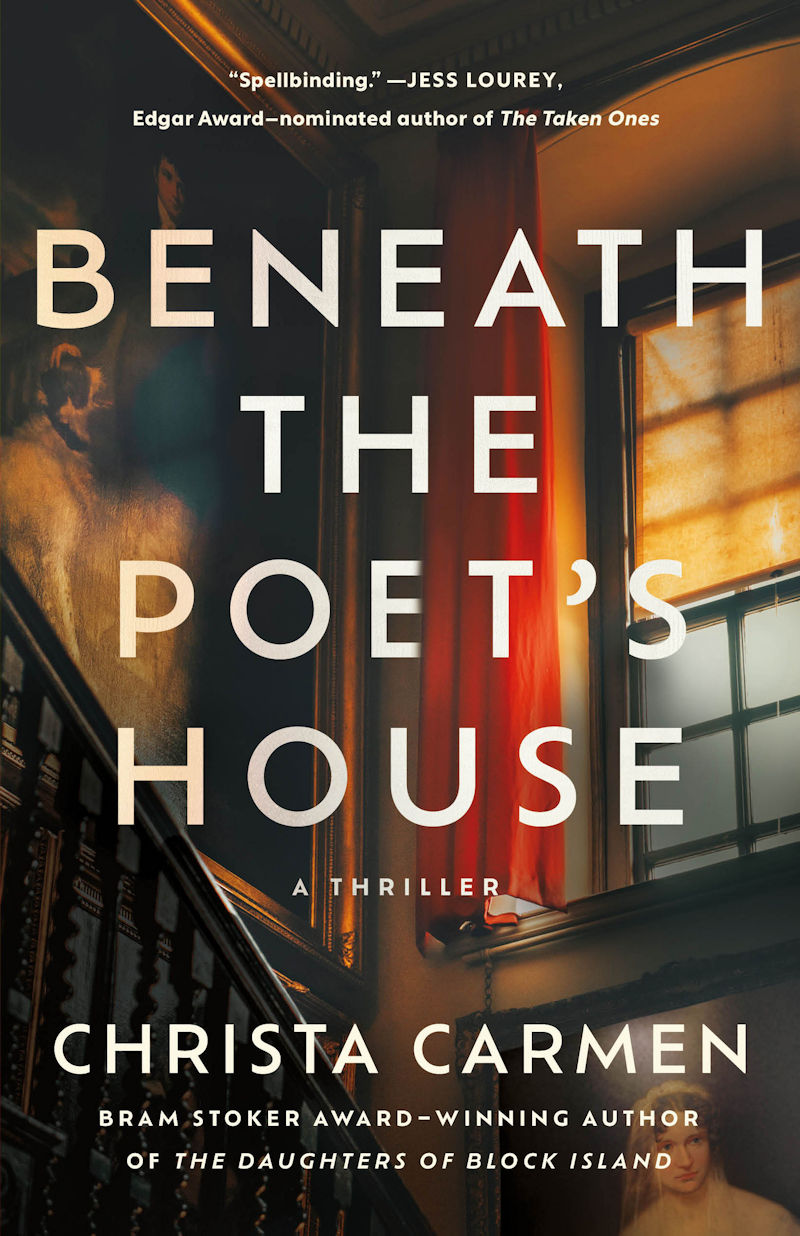

For a grieving writer, the secrets of the past and present converge in a novel of gripping psychological suspense from the author of The Daughters of Block Island.

Unmoored by her husband's death and suffering from writer's block, novelist Saoirse White moves to Providence, and into the historic home of Sarah Helen Whitman, the nineteenth-century poet and spiritualist once courted by Edgar Allan Poe. Saoirse's certain she'll find inspiration in the quiet rooms, as well as in the tucked-away rose garden and forgotten cemetery at the back of the property.

Saoirse is immediately welcomed by an effusive trio of transcendentalists obsessed with Whitman, the house, and Whitman's mystic beliefs. Saoirse, emerging from grief and loneliness, welcomes the idea of new friends taking her mind off the past?even as they hope to summon it. When she meets Emmit Powell, a charismatic and charming prize-winning author, Saoirse thinks she's finally turned a corner.

Anthology Showcase

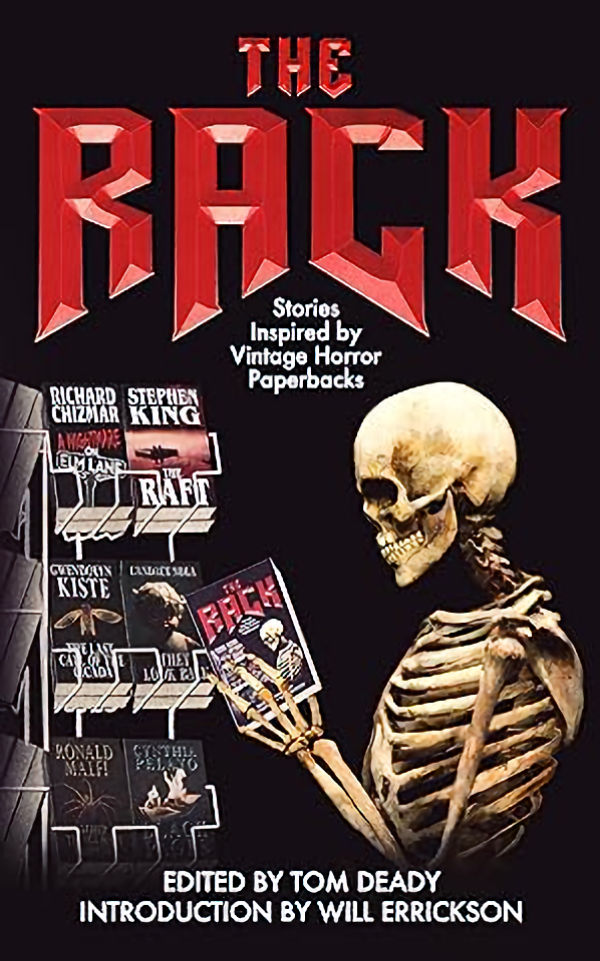

"Blood of My Blood"

The Rack: Stories Inspired by Vintage Horror Paperbacks

Greymore Publishing

Go ahead...spin THE RACK, if you dare. But don't say we didn't warn you.

Featuring stories by: Christa Carmen, Max Booth III, Clay McLeod Chapman, Richard Chizmar, Johnny Compton, Kristin Dearborn, Philip Fracassi, Laurel Hightower, Larry Hinkle, Stephen King, Gwendolyn Kiste, Ronald Malfi, Bridgett Nelson, Candace Nola, Errick Nunnally, Cynthia Pelayo, Rebecca Rowland, Jeff Strand, Steve Van Samson, & Mercedes Yardley.

Read More

The Rack: Stories Inspired by Vintage Horror Paperbacks

Greymore Publishing

Go ahead...spin THE RACK, if you dare. But don't say we didn't warn you.

Featuring stories by: Christa Carmen, Max Booth III, Clay McLeod Chapman, Richard Chizmar, Johnny Compton, Kristin Dearborn, Philip Fracassi, Laurel Hightower, Larry Hinkle, Stephen King, Gwendolyn Kiste, Ronald Malfi, Bridgett Nelson, Candace Nola, Errick Nunnally, Cynthia Pelayo, Rebecca Rowland, Jeff Strand, Steve Van Samson, & Mercedes Yardley.

Read More